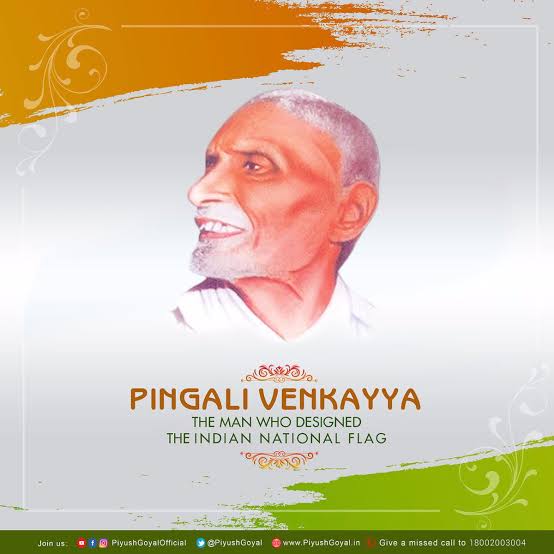

VIJAYAWADA: On August 2, 1878, a boy was born into a poor farmer family in Bhatlapenumarru village, Krishna district, near Machilipatnam. Pingali Venkayya was his given name, and he went on to be known as Patthi (Cotton) Venkayya, Diamond Venkayya, and Japan Venkayya. Jhanda (flag) Venkayya, on the other hand, is a name that will live on forever. Unsatisfied with the Union Jack being hoisted at every political gathering, Pingali resolved to design a national flag for India — a single flag that would not only shed light on the country's culture and traditions but also unite the people, which is what the Har Ghar Tiranga is all about.

But that wasn't all. 'National flag designer' was just another hat Pingali wore. There was more to him than the surface. Dr Venna Vallabha Rao, a Sahitya Academy award-winning writer and poet who also wrote the biography 'Jathiya Pataka Rupasilpi Pingali Venkayya' on the freedom fighter, describes him as a scientist without a degree. He believes there is a lot about the man that is unknown. The Union government issued a postal stamp commemorating Pingali's 146th birthday as part of the Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav.

Pingali was born in 1878, not 1876, as previously stated. So this year marked his 144th birthday. "We submitted a representation and informed the concerned officials, but they did not change it," Dr Rao tells TNIE. According to family members of Pingali, the freedom fighter was born in Pedakallepalli, not Bhatlapenumarru. "At the time Pingali was born, his maternal grandfather was a police constable in Peddakalepalli, and his father was a village administrator in Yarlagadda, near Challapalli." Pingali's grandfather moved to Bhatlapenumarru and Challapalli after being transferred. "He finished his primary education in these three locations," Dr. Rao explains.

Hindu high school in Machilipatnam

Hindu high school in Machilipatnam

Pingali attended the Hindu High School in Machilipatnam for high school. He was the eldest of five siblings in a large family. He did not want to burden his parents because he was a selfless person. Pingali used to stay as a guest with people who offered free lodging and food to students in Machilipatnam. He would eat at various houses. Pingali, at the age of 19, was moved by patriotism and decided to serve his country.

He travelled to Bombay, where he received training before joining the British Indian Army. He served in the South African Army during the Boer War, but it is unknown in what capacity. He met Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa around this time. Gandhi fought for equal rights for Indians living under British rule. Pingali and Gandhi remained friends for more than 50 years. Pingali developed a worldview during his time in South Africa. After witnessing the British's oppressive nature since childhood, his hatred and disgust for them grew. His desire to liberate India grew stronger with each passing day.

Pingali Venkayya, his wife Rukmanamma and his elder son Parsuramayya

Pingali Venkayya, his wife Rukmanamma and his elder son Parsuramayya

Pingali visited Arabia and Afghanistan on his way back from South Africa, analysing their political, social, and financial situations to better understand why India needed independence. Pingali became involved in the freedom movement after returning to India. "Gandhi was a Gandhian." He admired Bapu's commitment, patriotism, and perseverance in his fight for India's independence. Pingali, on the other hand, was a disciple of Bal Gangadhar Tilak. "He believed that rather than requesting freedom, one should fight for it," Dr Rao recalls.

Pingali had an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He wished to further his education in another country. He did odd jobs to save money because he didn't want to burden his family. He trained as a plague inspector in Madras and later worked in Bellary, Karnataka. He also worked as a railway guard on the Madras-Bangalore route, but he disliked both jobs. Pingali, the hardworking student, went to Colombo to study Political Economics. His plan was to research topics that would help the Indian economy.

Pingali's thirst for knowledge increased exponentially. He was fascinated by various Indian and foreign languages. "In 1904 at Dayanand Anglo-Vedic College in Lahore, he learned Japanese and began speaking quite fluently." He also studied Urdu, Sanskrit, and Hindi in Lahore. "He met national leaders fighting for independence," Dr Rao explains.

The unheralded hero was also a gifted orator. Congress leaders always gave him the opportunity to speak at public meetings. Pingali was the go-to man when microphones didn't work because he had a booming voice that could not only be heard by thousands but also keep them riveted.

An invitation changed Pingali's life in 1906, when he attended a meeting of the All India Congress Committee in Calcutta.

Rangarao Bahadur, the Zamindar of Munagala (now Telangana) in Krishna district, hired Pingali. Pingali was advised by the zamindar to focus on agriculture or administration. Pingali could earn money and pursue his dream of furthering his education in this manner. Pingali took the offer. He was interested in agriculture because his family was also involved in farming. He began conducting soil and crop research. His most important research was on how agriculture could help the country's economy.

Pingali concentrated on cotton in accordance with his research. Because the cotton harvested in India was thick, young people did not prefer it. They desired lightweight Videshi clothing. "Pingali researched and imported seeds from Cambodia and America with the goal of seeing youth wear India-made cotton clothing." "He used these seeds to create a new variety of cotton that became known as Cambodia Cotton," the biographer writes. The study earned him honours and a position at the National College in Machilipatnam, where he taught from 1911 to 1919.

Pingali moved back to Machilipatnam from Munagala and began teaching subjects such as soil fertility, history, physical education, NCC, and military training. His goal was to instil patriotism in students and help them understand India's freedom struggle and the importance of it. Pingali was over 30 years old at the time. People were not allowed inside their homes if they had crossed the seas back then. Pingali was allowed into the house, but he was not allowed to eat meals with his family. He left home and began living alone while working.

Being the family's eldest son came with a lot of responsibilities. Pingali had to marry because his brothers and sisters couldn't get married until he did. A reluctant Pingali married 10-year-old Rukmanamma at the age of 32. She was the daughter of a village administrator from Pamarru in the Krishna district. During his time as a lecturer at the National College, he researched various countries' flags. Pingali designed some models and published a book, 'A National Flag For India,' in 1916, after extensive research. Pingali emphasised the importance of a single national flag for the country during the numerous meetings he attended. Pingali got along well with national leaders such as Dadabhai Naoroji, Motilal Nehru, and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. He presented his ideas and solicited their feedback on designing the Indian national flag.

"In one of his columns, Mutnuri Krishna Rao, the editor of 'Krishna' newspaper, mentioned Pingali's book." "The newspaper emphasised the importance of translating Pingali's book into multiple languages for a broader audience," Dr Rao says. On March 31 and April 1, 1921, the first AICC meeting was held in Vijayawada (Bezawada at the time). It was held at Victoria Jubilee Hall, which is now known as the Bapu Museum.

In the interim, Gandhi knew about Pingali's endeavors to plan the public banner. He likewise had some awareness of Pingali's book on public banners. He welcomed Pingali to the gathering in Vijayawada. During this gathering, Gandhi talked about with Pingali the plan for the public banner. Pingali planned a banner according to Gandhi's ideas and introduced it to him at the gathering. After a couple of changes, the banner was taken on as the banner of the Congress and later, the turning wheel was supplanted with the Ashoka Chakra and raised formally as the public banner on July 22, 1947.

After Tilak's destruction in 1920, Pingali made a stride back from dynamic legislative issues. It's anything but an unexpected that he then, at that point, moved concentration to studies. He sought after courses in geography and mining. Till 1944, Pingali worked in the field of jewel mining at different spots. Pingali used to remain in Nellore, while his family and youngsters lived in Vijayawada. After India accomplished autonomy, Pingali moved to Vijayawada for good in 1948.

Pingali's more youthful child, Chalapathi Rao, was with the Indian Army. He got back in the wake of being impacted by tuberculosis yet passed on at a youthful age. Pingali and his better half were misery blasted. From 1948, Pingali inhabited Chitti Nagar close to Milk Project in Vijayawada. The public authority had provided Chalapathi Rao with a little plot of land, where Pingali resided in a covered house till he passed on in 1963.

His senior child, Pingali Parsuramayya, was a journalist with the Indian Express during the 1950s.

Pingali was in outrageous destitution in his last days, to such an extent that his family needed more cash to have food. For some time, his mastery in mining got him some cash. He was made a guide in the Mines Department and given an honorarium. Anyway by 1960, the post was renounced, and the honorarium was removed.

Indeed, Pingali and his family were left with nothing. Inquired as to why Pingali passed on in such penury despite the fact that he was an expert in a few fields, the biographer says, "Regardless of his fantastic information on various subjects, Pingali never involved it for bringing in cash. He worked to ultimately benefit society and individuals. He was a sacrificial nationalist, who never at any point looked for help from his colleagues even in critical conditions. Sense of pride and respect were his center characteristics."

Pengali Venkayya

Pengali Venkayya

Pingali had two wishes. One was satisfied, the other was not: he needed to see the banner lifted at Red Fort, however never could."Pingali kicked the bucket on July 4, 1963. Numerous Independence Days and Republic Days were commended somewhere in the range of 1947 and 1963, yet nobody at any point welcomed him to the occasions in Delhi. Heads of the state, Presidents and heads of a few different nations were welcomed, however not Pingali," Dr Rao doesn't conceal his mistake.

Pingali's last desire was to be enveloped by the public banner. He maintained that the banner should be attached to a peepul tree in the burial ground. "The wish was satisfied, however nobody appeared to mind when Pingali kicked the bucket. A couple of individuals from the city partook in the memorial service parade from Chitti Nagar to Vijayawada, when Pingali kicked the bucket," the biographer says. His 100-year-old little girl, Sitamahalakshmi, kicked the bucket on July 21, 2022, and was given a State memorial service.

Pingali journaled distributed research papers, and life story on Chinese pioneer Sun Yat-Sen and, surprisingly, his book, 'A National Flag for India'. Tragically, everything is lost. A corridor in Bhatlapenumarru, where Pingali was conceived, is the main commemoration in the unrecognized yet truly great individual's honor. This corridor, as well, was worked with the assistance of gifts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.