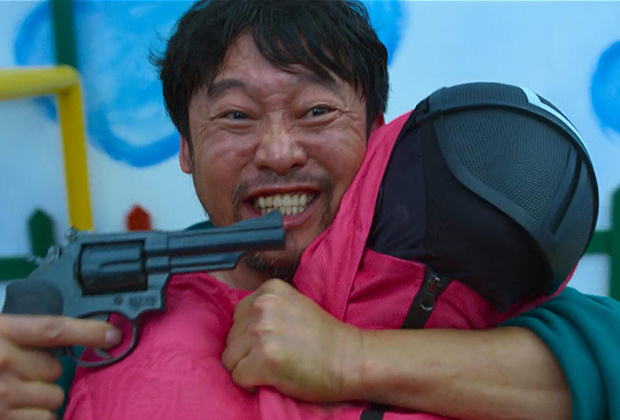

The main action of the show takes place in a giant secret complex on an unnamed island to which hundreds of marginalized people of all sorts are brought from all over South Korea. Among them are a washed-up Sung Ki-hoon (Lee Jong-jae), his childhood friend Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-su), a fugitive from the authorities for financial fraud, North Korean refugee Kang Sa-bok (Jung Ho-yeon), Pakistani migrant Ali (Anupam Tripathi) and gangster Jang-dok-su (Ho-sung-tae), who quarrels with his accomplices. All of them-not by compulsion, but by choice-are competing for a prize pool of 45.6 billion won ($38 million) in deadly versions of children's games. For example, in the very first competition, Silent Ride, Farther Away (or Red Light, Green Light), participants try to reach the finish line across a field while a giant puppet sings a song. When the song breaks off, anyone who keeps moving is mercilessly shot off.

However, the participants themselves do not mind reducing the number of competitors, staging at night ruthless carnage. To survive, they have to team up, but the friendship in the "Squid Game" threatens to serve a disservice - in any next game people can be forced to fight against each other. And there will only be one winner in this rat race.

Impersonal guards dressed in coral jumpsuits and masks keep order in the complex; they also act as the executioners of the losers. The organizers of the games are in hiding, but their goal is known: "to ensure an equal chance of success" for all the deprived and offended. The spectators of the show (as well as the beneficiaries) are international VIP guests who watch the bloodshed from the psychedelic lounge area, and, like the guards, also hide behind masks.

"Squid Game" has already become the most popular Korean drama in the U.S. and seems to be on its way to becoming a major hit on Netflix worldwide. The reasons why the series has become the most-watched service project in 90 countries are obvious - there's the characters with elaborate stories that are easy to empathize with and the unusual setting like hypertrophied playgrounds, colorful mazes and stair towers a la "Hogwarts for kids" and contrasting with this rainbow, generally unaccustomed to Western TV bloodthirstiness of the show. The latter manifests itself, of course, in the incredibly tense death-defying tasks based both on the world-wide spread and on games known only to South Koreans as children's games.

The battle royale genre in film and television has existed for decades - its founder was the 2000 Japanese film "Battle Royale" by Kinji Fukasaku, in which the government sent schoolchildren to an island, forcing them to kill each other. There are enough representatives of this genre in the West as well - the Hunger Games and Judgment Night franchises have pitted their characters in bloody and fierce battles for more than one movie. Nor was "Squid Game" Netflix's first attempt to introduce the world to doramas, including in the survival genre-the year before the streaming service released the Japanese "Alice in the Frontier," which did not, however, achieve the same fame. The hyper-violence of "Squid Game" in general is not new for doramas - for example, the Japanese series "Tokyo Vampire Hotel" by Sion Sono (author, by the way, of the fresh madness "Prisoners of Ghostland" with Nicolas Cage) in 2017 elevated mass bloodletting to the degree of the highest absurdity.

But all of these films and TV series are missing one component, the one that made The Squid Game bathe in acclaimed reviews and win the audience's sympathy. If "Battle Royale" and the novel on which it is based depicted the clash between the fascist state and the youth (the book was written by Cosun Takami, inspired by the global wave of student protests of the late '60s, which took place in Japan, among other places), "Alice in Frontierland emphasized CGI graphics and plenty of "unexpected" (in fact, very predictable) plot twists, while Tokyo Vampire Hotel massacred young and hopelessly lonely people, the new series takes on the theme of social inequality.

All of the leading characters are people who, for various reasons, find themselves on the margins of life, forced to cheat, betray and even kill each other for money

This theme was anticipated in 2019 by South Korean director Pon Joon-ho's "Parasites" (also a resounding worldwide success, and it took almost all of the Oscars). Well, "Squid Game" organically built it into the battle royale framework with rivers of blood and outright sadism towards its own heroes, which had already repeatedly proved its popularity with the general public. The mix turned out to be truly explosive - and the fashion for anti-capitalism that gripped popular culture played into the hands of the series.

With the advent of a pandemic that has only further exposed the vast gulf between social classes, celebrities - having been burned more than once by attempts to equalize themselves with their fans - have expropriated this class tension in their own way, creating a truly absurd world in which congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez appears at the Met Gala ultra-light ball in New York wearing a gorgeous dress, in which Congresswoman Alexandria Ocio-Cortez appears in a lavish dress embroidered with the slogan "Tax the Rich," in which singer Grimes, having a child with the richest man on the planet, walks down the street with "The Communist Party Manifesto" and jokes about creating a lesbian space commune, and in which the ancient slogan "Eat the Rich" is renaissance both in political rallies and in social networking memes. In short, mass culture is also ready to requisition such a creepy thing as the stratification of society through amazing metamorphosis, and The Squid Game has been on top of the wave of this strange trend.

The problem is that it is the social agenda that the show uses more as a justification for spectacular torture-the conflict between the rich and the poor is outlined here quite unequivocally, but in an extremely superficial way.

For example, for all the impersonality of the executioners surrounding the characters, the show still has obvious antagonists: arrogant, painfully caricatured VIP guests, for whom the lives of the poor represent only a moment's entertainment. By introducing these characters into the plot, Squid Game immediately pushes the idea that only scumbags can have a lot of money; this message is reinforced in the show's finale, when the characters descend into clichéd scenes like an argument about whether unselfishness can beat greed, and the main character's "we are not horses" line.

For example, for all the impersonality of the executioners surrounding the characters, the show still has obvious antagonists: arrogant, painfully caricatured VIP guests, for whom the lives of the poor represent only a moment's entertainment. By introducing these characters into the plot, Squid Game immediately pushes the idea that only scumbags can have a lot of money; this message is reinforced in the show's finale, when the characters descend into clichéd scenes like an argument about whether unselfishness can beat greed, and the main character's "we are not horses" line.

In Parasites, which, balancing between comedy and horror, showcases the horrors of social stratification, Bong Joon-ho deliberately does not label characters based on their social status, emphasizing that it is the class divide, not its representatives, that suffers. In The Squid Game, showrunner Hwang Dong-hyeok, by contrast, limits himself to populist ideas about the rich pitting the poor against the poor to ensure the status quo, about power and money corrupting and depriving the human form - hence the compound guards hiding their faces and VIP guests even walking around in golden animal masks.

Instead of engaging in any meaningful dialogue about social problems, Squid Game focuses on the torture of its characters for the enjoyment of its audience, which, it turns out, is much closer to the VIP audience than the numbered marginalized, who are aroused and aghast by their ordeal. And it's not surprising, really - going back to the depths of world television's history of less bloody but no less dehumanizing reality shows, they obviously don't need a separate introduction. "Squid Game," which at first glance is a critic of this phenomenon because it draws parallels between it and class oppression, is in fact an apologist for it, exploiting the same techniques. Fortunately, in a playful format.

You must be logged in to post a comment.